My

name is John Akinola and I work as a car guard. You may have seen me earlier,

but you chose not to look. Most people don’t make eye contact when they drop a

fistful of coins into my palm. I don’t blame them, and I am grateful my mother

is not here to witness this. I know you are busy with your shopping and your

errands, but I want you to hear my story.

On

the day I was born, my mother was doing washing in the river.

“There

was a terrible pain in my belly just here,” she’d say, pointing at her pelvis.

“And I was beating the blanket with a stone. Every time I felt pain, I would

beat harder.” She would laugh at the memory. “And then you arrived! You fell

out like a piece of soap – boh! –

into the river. Just like John the Baptist.”

I

never told her that they called me John the Bastard at school.

Then

she would take my face in her hands, knuckles bulging with arthritis, and say,

“Johnny, when you are afraid you must remember that you slipped into this world

and you can slip out of it at any time. Don’t let fear stop you from doing what

you know in your heart you must do.”

She

was, of course, justifying the course of her life to me. My father was a truck

driver and never knew of my existence. She told me how she fell in love with

him under a tree. He bought her orangeade and stroked her cheek.

“I

was so happy, Johnny. I never understood what it meant to be swept off my

feet until I was lying on my back and making you.”

I

have often wondered whether I have half-brothers and sisters scattered across

the highways between Lagos and Mombasa. As a child I had dreams of finding my

father by meeting them, the human breadcrumbs on the trail to where he lives.

My grandfather was the one with the wisdom to know better and talked me out of

my fantasy.

“And

what will you say to him when you get there? ‘I am your son’? He will laugh at

you, boy. Your family is here. I am your family.”

“He’s

only a boy.” My mother kissed my hair.

“Yes,

and you were only a girl but here we are.”

I

don’t think my grandfather ever forgave my mother. He said she had an

incomplete schooling, which meant she was good for nothing but serving others.

She worked in the Hallerman Hotel as a maid and, although it paid well, it

meant I rarely saw her. To me it seemed as though my grandfather tolerated my

mother when he should have loved her.

“Johnny,

listen to me,” he’d say, “whatever you do with your life, find something you

enjoy.” My grandfather was standing behind the counter of his tuck shop,

straightening the packets of sweets on the shelf.

“Where

do I find it?”

He

poked my chest. “In here.” He pointed to the street. “Look. Look!” He would

check that my eyes followed his finger. “Those people are all dead inside. They

are poor and unhappy and living a pointless existence. Do you see, boy?”

I

nodded.

He wiped

his eyes. “I had dreams once. Before you were born. It’s too late for me. Too

late for your mother. It’s up to you now, John. Find out what your purpose in

life is.”

“But

I don’t know how.”

He

slapped me. “Haven’t you been listening?”

I

nodded, but only because I didn’t want him to hit me again. I kept my eyes on

the street, hoping to spot the answer there.

“Johnny,

come and help me with this.” He pointed to the packets of potato chips.

I

began arranging them according to their flavours: salt and vinegar, tomato,

cheese and onion.

“Good.

Keep it up. I am going around the corner.” That was his code for using the

bathroom.

It

was a kind of meditation to pack the shelves. I moved on to the lollipops next,

then the bags of tobacco and matchboxes. The dust smelt of cardboard boxes left

to grow mould in a garage. I thought about what my grandfather said, but no

answers revealed themselves.

That

night, we sat in silence while we ate. My grandfather decided to forego his

routine of preaching to us about missed opportunities.

“Did

you help your grandfather in the shop today, Johnny?”

I

nodded.

“Was

it busy?”

He

grunted.

“I’ve

had a letter from Sister Magenta. She thinks Johnny should start school there

next month.”

“What

for?” He sprayed the table with crumbs.

“He

is clever. They say he will get a good education. He could get a job in the

city.”

“With

the nuns? All Johnny will learn is about crossing himself and sin. No. He stays

where he is.”

“I

think it will be good for him to go. You are the one who is always telling us

about making a better future.”

“Ah,

yes. Blame me. And when the boy comes back here with pictures of a white man

and talking about heaven, what will you say then?”

“I

want to go.”

My

grandfather still had his fist in the air, and the sinews in my mother’s neck

were taut.

“What?”

“Good

boy, Johnny.”

“No,

I said no. You will regret this just like you will regret that night with the

trucker man.”

“Ah,

ah. It always comes back to that. I do not regret that. I regret that I was

born with you as my father.”

“You

regret! I regret...”

I did

not stick around to hear the rest of their argument. It always went the same

way and one of them ended up crying.

The following

weekend, I watched my mother pack my bag for the bus ride to the school. My

grandfather came into the room, patted me on the head and then said he had to

go out. That was his version of goodbye. I observed my mother as she folded my clothes and

placed them like hallowed loaves into my bag. She was murmuring to me about my

manners and being grateful, but I would never get the chance to use her advice.

About

twenty minutes after we left my mother waving in the dust, our bus broke down.

Sixteen men arrived and took all the young people, like me, and our luggage. We

were going to take a different route, they said. A short cut. I saw their

machetes and decided not to argue. They gave us water to drink and

when I woke up we were locked in the back of a truck. The girls were the only

ones who were allowed to get out at the rest stops. Their screams made me

grateful that I could stay. Ten days after I left my mother, I arrived in your

country.

I

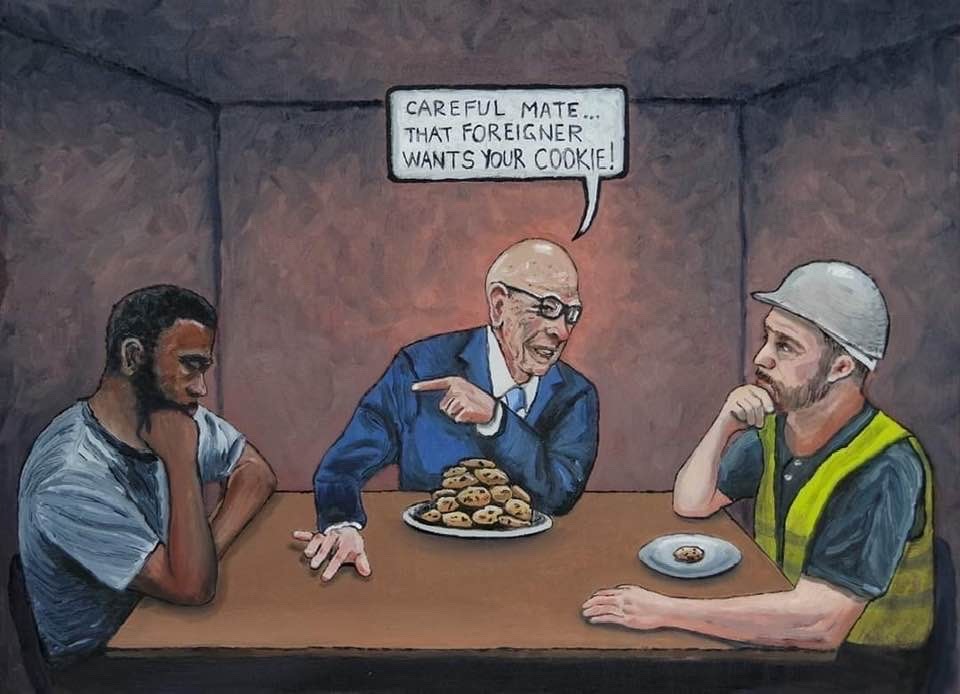

know I have been talking for a long time already, but please let me have a few

more minutes. Somebody said once that the only certainties in life are death

and taxes. I can think of two more: greed and foreigners. Greed is a great

motivator, you see. It follows the pattern of see, want, get – or take, in some

contexts. Greed is the cornerstone of humanity and everything we do is

motivated by the desire to acquire. Even if it is only food or sleep. Why

foreigners, you ask? Because at some point, we will all be outsiders to a place

or situation. We will all have the jitters on the first day of a new job or

going to a new place – you know what I mean.

So, my

being here, watching your car and taking your spare change, is not because I

dreamt this for my life. Please remember that. Now, can I take your trolley?

No comments:

Post a Comment